Martin Puryear - Between Craftsmanship and Art

Aug 23, 2017

The works of Martin Puryear emit a sort of aesthetic gravity. They attract our attention with their presence, pulling us toward them with implicit promises of beauty, comfort, and after looking at them for a while, even understanding. Born in 1941, Puryear has been making things with his hand since he was a child. He can build a guitar or a boat by hand. He works in upstate New York in a studio that he built himself, often using natural materials for which he foraged, shaped with tools that he made. The hand made aspect of his sculptures has earned Puryear the reputation of being a true artisan: someone devoted to the traditions of craftwork, who is deserving of the reverence such difficult work commands. But it is his ability to project the universalities contained within the objects he makes that has earned him the reputation of being one of the greatest living artists in the United States. Many of his works are untitled and considered abstract, but their essence is unmistakable. Though we may not be able to name them, they may well possess a clearer idea of what they are than we have about the nature of ourselves. With a major exhibition of his work opening 19 September at Parasol Unit Foundation for Contemporary Art in London, we thought we would take a deeper look at Martin Puryear, and offer some background on his fascinating life and work.

The Bio-Minimalist

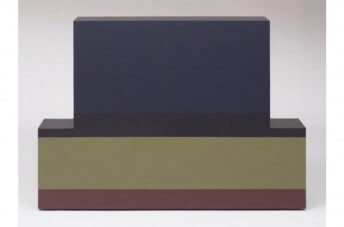

Forgive me for coining what may be nothing but useless art slang, but here is a word I made up to describe the work of Martin Puryear: Bio-Minimalism. What I mean may be obvious, but in case it is not, let me explain: I mean the objects Puryear makes are minimalistic in their essence—to borrow from Donal Judd, they are specific objects; orderly, unified and powerful—but they are also packed full of the inherent narrative content inherent within biological reality. They can be defined as self-referential things, and appreciated according to the materials and processes that led to their creation. But they are also complex, and that complexity plays a major role in validating their quality. They are possessed by their own craftsmanship. They are obviously made by a human, and the toil, intellect, vision and personality of that human are an essential part of what makes them interesting.

While earning his MFA from Yale, Puryear was trained in part by two artists who themselves helped elucidate the meaning of Minimalism: Richard Serra and Robert Morris. But whereas such artists might eschew personal craftsmanship and opt instead to have objects manufactured, Puryear would prefer to walk into the woods, cut a tree down, cut and dry the wood in his studio then shape it with tools he made the same way. Whereas a purist Minimalist might conceive of a specific form ahead of time then have it built using materials and processes devoid of content or emotion, Puryear chooses materials that express their history, guiding them toward the manifestation of their aesthetic inevitabilities. Whereas a Minimalist might strive to make meaningless, useless things, Puryear strives to make things that contain the same richness, texture, and poetic substance as their raw materials. As intimately connected to the natural world as they are, they can never be meaningless, nor useless. And since we share their origin they cannot fail to attract our interest.

Martin Puryear - Sanctuary, 1982, Pine, maple, and cherry (Left) and Night Watch, 2011, Maple, willow, OSB board, image courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery, photograph by Christian David Erroi (Right)

Martin Puryear - Sanctuary, 1982, Pine, maple, and cherry (Left) and Night Watch, 2011, Maple, willow, OSB board, image courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery, photograph by Christian David Erroi (Right)

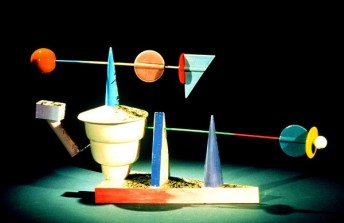

Multi-Disciplined and Universal

Puryear is best known for his sculptures and his public works. His monumental outdoor work Box and Pole, created in 1977, remains to this day one of the most elegant and straightforward expressions of his aesthetic position. And his Ladder for Booker T. Washington from 1996 has become an iconic contemporary statement, revered for its abstract qualities, its material aspects, the meticulous process of its creation, and its narrative historical implications. But since the 1960s, Puryear has also been working consistently in the medium of printmaking. He first learned to make prints at the Royal Swedish Academy of Arts in Stockholm, where he studied after serving as a teacher for two years in the peace Corps, in Sierra Leone. Many of his prints, along with many other artworks, were lost in a fire in his Brooklyn studio in 1977. But some were saved and either repaired by Puryear or reworked by him in new ways.

Martin Puryear - Question, 2013-14, Bronze, 87½ x 107 x 34¼ in, image courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Martin Puryear - Question, 2013-14, Bronze, 87½ x 107 x 34¼ in, image courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

For the upcoming exhibition at Parasol Unit, curator Ziba Ardalan has set aside a separate gallery on the first floor of the museum in which to showcase the printmaking aspect of his practice. His prints reveal a careful touch and a rustic aesthetic that adds depth and layers to his overall oeuvre. They will be a surprise to many fans who only know Puryear for his sculptures. But worry not, those hoping to enjoy personal encounters with the sculptural objects for which Puryear is famous will also not be disappointed. On view in Martin Puryear at Parasol Unit will be a range of sculptures representative of the full breadth of materials and processes Puryear employs. Included will be bronze and iron works like Question and Shackled, contemporary wooden works like The Load (2012) and Night Watch (2011), as well as older wooden objects like Believer (1977-82). The exhibition will be on view from 19 September through 8 December 2017 at Parasol Unit Foundation for Contemporary Art, located at 14 Wharf Road, London.

Martin Puryear - Question, 2013-14, Bronze 87½ x 107 x 34¼ in, image courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery, photograph by Christian David Erroi

Martin Puryear - Question, 2013-14, Bronze 87½ x 107 x 34¼ in, image courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery, photograph by Christian David Erroi

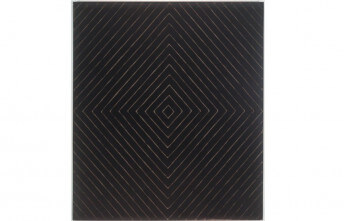

Featured image: Martin Puryear - Eastern white pine, mesh, tar, image courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

All images © Martin Puryear; All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio