How Victor Pasmore Found His True Style in Abstraction

Aug 14, 2017

This coming January will mark the 20th anniversary of the death of Victor Pasmore, a pioneer of British abstract art. Pasmore underwent a unique transformation over the course of his artistic career. As a young pupil he studied the works of the early Modernist masters. Inspired by artists like Picasso and Braque, he taught himself their techniques by spreading reproductions of their works around him on his floor and copying their compositions. But after becoming dissatisfied with such stylized approaches to painting, Pasmore suddenly rejected the ideals of Modernism, going so far even to institute a new program at the school that he helped run, requiring his students only to paint from life in a naturalist way. But then a series of dramatic life events led to yet another shift in perspective for Pasmore. After the breakout of World War II, he enlisted briefly in the army. He quickly deserted and was subsequently arrested and thrown in jail until the intervention of a wealthy patron helped get him released from prison. And that is when Pasmore became interested once again in the roots of Modernist aesthetic traditions. He began reading the writings of the great Post-Impressionist painters, and became inspired by their advanced ideas, which he came to believe they had not fully realized in their works. He decided to start where they had left off, abandoning naturalist art and embracing the mystery of abstraction.

Early Abstract Works

From his days as a student, Victor Pasmore knew that he learned best by studying the works of other great artists. It was in that same spirit that he underwent his initial transformation into an abstract artist. Rather than jumping right in to non-objective imagery, he mimicked the development of the Post-Impressionists, whose efforts had led the way for the pioneers of abstraction. Pasmore taught himself Pointillism and other such approaches they had developed, discovering for himself, as they had, what painting is, and what ultimate purpose it might possess. By the late 1940s, his transformation was complete. Pasmore had reduced his visual language to include only the simplest of shapes and patterns, such as squares, spirals, circles and lined patterns, and a pared down selection of colors.

But rather than embracing the mystical leanings of early abstract art pioneers like Wassily Kandinsky, Pasmore was drawn toward the secular ideas embraced by the early Constructivists. He concerned himself with the formal qualities of abstraction, focusing on the material properties of his works and their presence within physical space. He also became interested in the idea that artists should strive to make work that has a public purpose. His ideas were somewhat revolutionary for Post War Britain. But as an active and influential teacher, Pasmore influenced many other British painters to consider these same points of view, and quickly he became a pioneer in a British Constructivist movement that eventually included influential painters such as Terry Frost, Anthony Hill and Kenneth Martin.

Victor Pasmore - Senza Titolo, 1982, Etching and Aquatint, 35 × 94 cm, photo credits Marlborough London, London

Victor Pasmore - Senza Titolo, 1982, Etching and Aquatint, 35 × 94 cm, photo credits Marlborough London, London

Expanding Into Architecture

Undergoing yet another experimental transformation, in the early 1950s, Victor Pasmore abandoned two-dimensional art in favor of exploring the three-dimensional aspects of constructivism. He started making reliefs that hung on the wall, and then expanded that concept outward into what he called hanging reliefs, which resemble mobiles made from geometric, mostly rectangular forms. His constructions were reminiscent of architectural studies, a fact that soon inspired Pasmore to start thinking in terms of translating his artistic ideas into the public sphere by designing buildings. And in 1955, he received a rare opportunity to combine his architectural ambitions with his constructivist ideals.

Victor Pasmore - Abstract in White, Black and Natural Wood, 1960-1961, Black chalk and oil on wood, 52.1 × 48.9 cm (Left) and Projective Relief Painting in White and Black with Pink, Green and Maroon, 1982, Paint on panel, 121.9 × 121.9 cm (Right), photo credits Marlborough London, London

Victor Pasmore - Abstract in White, Black and Natural Wood, 1960-1961, Black chalk and oil on wood, 52.1 × 48.9 cm (Left) and Projective Relief Painting in White and Black with Pink, Green and Maroon, 1982, Paint on panel, 121.9 × 121.9 cm (Right), photo credits Marlborough London, London

Like the rest of Europe, Britain was engaged actively in the building of new towns following World War II. When a rural mining community came together and requested a town be built for them, Pasmore was named the Consulting Director of Architectural Design for the new town. Named Peterlee, the town eventually adopted many aesthetic themes reminiscent of the ideas Pasmore developed in his art. His most lasting impact is a central pavilion that connects the two halves of Peterlee and acts as a pedestrian bridge over a scenic lake. Named the Apollo Pavilion, it is a striking modernist construction, made of poured concrete and constructed on sight. Pasmore called the Apollo Pavilion, “an architecture and sculpture of purely abstract form through which to walk, in which to linger and on which to play, a free and anonymous monument which, because of its independence, can lift the activity and psychology of an urban housing community on to a universal plane.”

Victor Pasmore - Apollo Pavilion (aka Pasmore Pavilion), © Victor Pasmore

Victor Pasmore - Apollo Pavilion (aka Pasmore Pavilion), © Victor Pasmore

A Return to Free Expression

Gradually Victor Pasmore returned to painting, relaxing his self-imposed guidelines and incorporating a wide range of media and techniques into his work. In the late 1960s, he moved to the island of Malta off the coast of Sicily. There, over the last few decades of his life, the intense, studious rigor that had defined his earlier struggle to grasp the origins of abstraction gave way to a return to freedom. His works from that time fluctuate between loose, gestural lyricism and structured, geometric compositions. Often they carry titles that evoke a clear connection with their imagery, not in a purely naturalistic way but not in an entirely abstract way either.

When he died in 1998, Pasmore left behind a large collection of works that he had retained and stored in his house in Malta. Those works were discovered soon after his death, and today are permanently displayed in a gallery housed in the Central Bank of Malta. Along with the Apollo Pavilion, which, after falling into disrepair after decades of abuse and neglect was completely restored in 2009 and can now be visited any time, the Malta gallery offers an excellent opportunity to experience the work of this influential artist, who, as a founder of British Constructivism, was a groundbreaking pioneer of British abstract art.

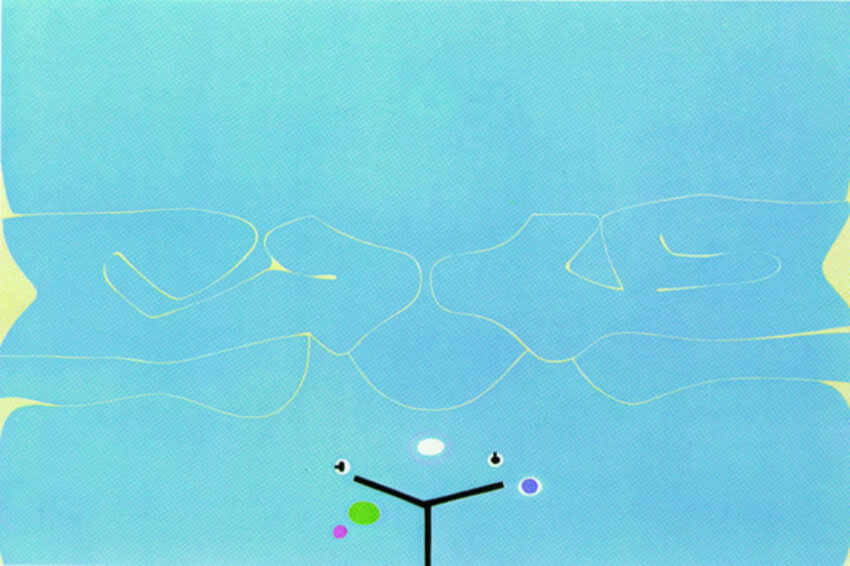

Victor Pasmore - Soft is the Sound of the Ocean, 1986, Etching and aquatint, 100 × 167 cm, photo credits Marlborough London, London

Victor Pasmore - Soft is the Sound of the Ocean, 1986, Etching and aquatint, 100 × 167 cm, photo credits Marlborough London, London

Featured image: Victor Pasmore - Punto di Contatto 5, 1982, Etching and aquatint, 51 × 72 cm, photo credits Marlborough London, London

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio