At LACMA, Sarah Charlesworth Presents Doubleworld

Aug 25, 2017

The Pictures Generation sounds like a great name for children born today. Never before in history have so many people had immediate access to picture-taking technology, along with the ability to share pictures instantly across the globe. But the term actually refers to a group of artists, including Sarah Charlesworth, John Baldessari, Sherrie Levine, Laurie Simmons, Cindy Sherman, and dozens of others, who took strides 40 years ago to understand and critique the role pictures play in the formation of human identity. Today we are so inundated with pictures that it almost seems quaint to see them as something separate from reality. Everywhere we look there is a device or a surface connected to a steady stream of pictures of the world as it is, as it was, as it could be, as it should be, as it never was and never will be. Only the least sophisticated among us do not take it for granted that every picture we see could have been manipulated, and a growing number of us simply assume that every picture we see is fake. But 40 years ago, that was not the case. No one was walking around with a portable camera phone back then. Photo manipulation was not easy, nor was access to pictures from other places immediate. People were cynical, but not necessarily about pictures. But the industry that eventually grew into that which so effectively controls our way of seeing today was definitely beginning to hit its stride, and the artists that were part of the Pictures Generation were pioneers in the quest to understand it. Sarah Charlesworth: Doubleworld, a new exhibition that opened this week at LACMA, offers a rare chance to delve deep into the legacy of the Pictures Generation by examining a monumental selection of work from one of its most influential pioneers.

A Picture of Mid-20th Century America

Sarah Charlesworth was born in 1947, in East Orange, New Jersey. Like every other member of her generation of Americans, she was raised in a Post War world of mass production, suburban expansion and consumerism. Social and political changes were occurring across the country in every sphere. American home life was changing, as was community life, business life, and national life. And all of those changes really had to do with one thing: identity. How people saw themselves was important, and it was even more important how they were seen by others. As with today, the primary way the American concept of identity was being formed back then was through pictures. Television showed images of what a successful man looked like, a fulfilled woman looked like, and a good citizen looked like. Newspaper photographs showed what tragedy, glory, war, crime and accomplishment looked like. Print advertisements portrayed a magical world just off to the side of all that other stuff, full of glistening products, smiling faces, and realized dreams.

Sarah Charlesworth: Doubleworld, installation view, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, August 20, 2017–February 4, 2018, art © Estate of Sarah Charlesworth, photo © Museum Associtates

Sarah Charlesworth: Doubleworld, installation view, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, August 20, 2017–February 4, 2018, art © Estate of Sarah Charlesworth, photo © Museum Associtates

Meanwhile, the art world was busy all but abandoning its belief in realistic pictures. Conceptual artists were busy proving that the idea was supreme over the image. Land artists, light and space artists and performance artists were demonstrating to our delight how processes and ethereal aesthetic phenomena were more vital, more contemporary, and more powerful than pictures. Painting still persisted, of course. But most of what made waves in painting in the 1950s and 60s was abstract. Painting was about processes, materials, and formal concerns. Painted images of the real world were considered old fashioned, and somewhat pointless. But then as the 1960s came to a close, an irony began to become apparent to many philosophers, artists and social critics: not only had art become more abstract, but the pictures pouring in to the average American household also had begun to have almost no relationship to concrete reality whatsoever. The pictures on which most people were basing their identities and their opinions of each other were fabrications.

Sarah Charlesworth: Doubleworld, installation view, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, August 20, 2017–February 4, 2018, art © Estate of Sarah Charlesworth, photo © Museum Associtates

Sarah Charlesworth: Doubleworld, installation view, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, August 20, 2017–February 4, 2018, art © Estate of Sarah Charlesworth, photo © Museum Associtates

Taking Appropriate Steps

Sarah Charlesworth was one of the pioneers who questioned the power mass media pictures were having over contemporary humanity. She saw the pictures in the paper, on the TV, and in the magazines and realized that they were, in a sense, no different than the pictures in museums. She saw that every picture that exists in the world right now is, in a way, the possession of every person who can see it. It can be used, interpreted, manipulated and conceptualized in endless ways by that person. The authorship of the picture maker is therefore perhaps irrelevant, because as soon as the picture exists it is possessed by the public and can be used for other reasons. Creativity and originality, she therefore realized, were becoming obsolete. And what that basically amounted to is the idea that an artist needs not invent new pictures. An artist can simply use the images that already exist as a raw material for new art.

Sarah Charlesworth: Doubleworld, installation view, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, August 20, 2017–February 4, 2018, art © Estate of Sarah Charlesworth, photo © Museum Associtates

Sarah Charlesworth: Doubleworld, installation view, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, August 20, 2017–February 4, 2018, art © Estate of Sarah Charlesworth, photo © Museum Associtates

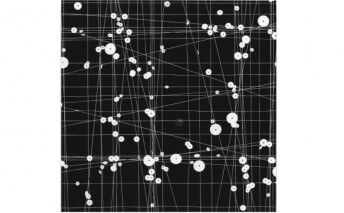

The contemporary word for this concept is appropriation. The first body of work Charlesworth created that explored the idea of appropriation was called Modern History. For this series, she collected 29 North American newspapers and photographed their front pages. She eliminated everything from the images except the masthead of the paper and whatever pictures were on the page. The result was front page news as communicated only through images. By appropriating one of the most common sources of media at the time, she challenged the nature of authorship and the importance of originality. But more than just that, she also forced viewers to contemplate what is being communicated by pictures. If newspaper photographers have done their job well, their pictures should tell a story. But what story do those pictures tell? What context is lost by eliminating the words? The idea was to challenge the viewers to think more deeply about how they interpret the pictures they see.

Sarah Charlesworth: Doubleworld, installation view, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, August 20, 2017–February 4, 2018, art © Estate of Sarah Charlesworth, photo © Museum Associtates

Sarah Charlesworth: Doubleworld, installation view, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, August 20, 2017–February 4, 2018, art © Estate of Sarah Charlesworth, photo © Museum Associtates

Doubleworld

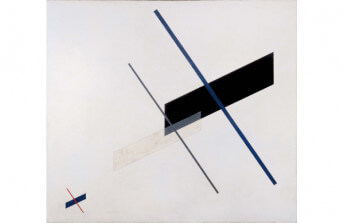

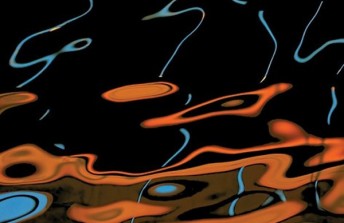

That first series of newspaper appropriations is just one of the ten bodies of work by Charlesworth that is currently on view at LACMA. Among the other series on view is her series 0+1 (2000), which involves all-white objects photographed in front of white backgrounds flooded with light, challenging the perception of the viewer by showing only a hint of the subject; Neverland (2002), which involves objects photographed on monochromatic backgrounds, isolating the subject in order to present as an icon of its own form; Figure Drawings (1988/2008), which features 40 photographed images of human figures; Objects of Desire (1983–89), which fetishizes images taken from other sources, placing them in isolation on brightly colored backgrounds; and the series Stills (1980), perhaps her most controversial body of work, which features cropped, rephotographed and enlarged newspaper photographs of people falling off of buildings, either because they committed suicide or because of a fire or some other emergency. Also included is her series Renaissance Paintings (1991), which features isolated fragments of actual Renaissance paintings rearranged to re-contextualize their narratives. About this series, Charlesworth once made a comment that sums up much of what her work is about. She said the series is not about Renaissance paintings, it is about the fact that “we live in a world where Renaissance paintings exist.”

Sarah Charlesworth: Doubleworld, installation view, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, August 20, 2017–February 4, 2018, art © Estate of Sarah Charlesworth, photo © Museum Associtates

Sarah Charlesworth: Doubleworld, installation view, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, August 20, 2017–February 4, 2018, art © Estate of Sarah Charlesworth, photo © Museum Associtates

The subtitle for the LACMA exhibition, Doubleworld, is taken from a series of works Charlesworth created in the 1990s, which is also included in the show. It was one of the few bodies of work Charlesworth created that involved her taking original photographs of three-dimensional objects. The series includes photographs of double-sided cabinets, each side filled with objects as in a still life. The objects chosen often relate to photography, such as cameras or old photographs. The series has a larger point to it, which translates well the idea of this exhibition. That is to say it speaks to the notion that we live in an environment that contains at least two different worlds. One is the world of reality, and one is the world of pictures. Images are not reality, though they may show pictures of things that exist. Even though that seems obvious, that pictures are not real, we nonetheless interpret them in ways that directly affect our reality. By showing us pictures of pictures and pictures of cameras, Charlesworth stated that pictures and picture making machines are as valid as any other subject matter. And yet at the same time, she pointed out by manipulating our experiences of her images that interpretation is vital to our understanding of pictures, and vital to how we let them shape our identity. Doubleworld reminds us that the meaning of this world relies heavily on how we interact with the world of pictures, and how we regard the intentions of those who create it. Sarah Charlesworth: Doubleworld is on view through 4 February 2018 at the Art of the Americas Building, Level 2, at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Sarah Charlesworth: Doubleworld, installation view, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, August 20, 2017–February 4, 2018, art © Estate of Sarah Charlesworth, photo © Museum Associtates

Sarah Charlesworth: Doubleworld, installation view, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, August 20, 2017–February 4, 2018, art © Estate of Sarah Charlesworth, photo © Museum Associtates

Featured image: Sarah Charlesworth: Doubleworld, installation view, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, August 20, 2017–February 4, 2018, art © Estate of Sarah Charlesworth, photo © Museum Associtates/LACMA

By Phillip Barcio