Artist Gerson Leiber Dies Hours Before His Wife Judith—A Look at Their Legacy

May 7, 2018

Gerson Leiber is reported to have painted every day for more than seven decades. That streak ended on 28 April 2018, when Leiber died of a heart attack just hours before his wife Judith, to whom he was married for 72 years, died the same way. The Leibers lived an almost unbelievably full life, hobnobbing with celebrities and traveling the world to exhibit their work. And yet they came from almost abject poverty and nearly had no life together at all. They met in the most unlikely way in Budapest at the end of World War II. Judith was from a Jewish family but had avoided the nazi concentration camps only due to her skills as an artisan. Intent before the war on putting her skills to use in business, the Nazis put her to work making things for them. When the war ended, she began selling custom handbags on the street. That is how she met Gerson, who was a sergeant in the United States Army and was in Hungary as part of a liberating force. Gerson asked Judith on the spot to accompany him to the opera. She said yes. Gerson confided in Judith that he had wanted to be an artist before the war. Judith encouraged him to enroll in art school in Budapest, which he did. The couple soon after married, and in 1947 moved to New York together. They had few resources, but the one thing they both knew for certain was that they would devote their lives to creativity—Judith would make and sell her own handbags, and Gerson would be a painter.

Painting His Time

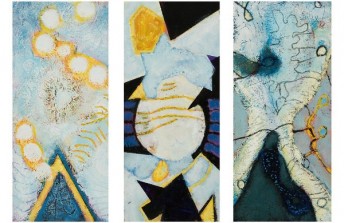

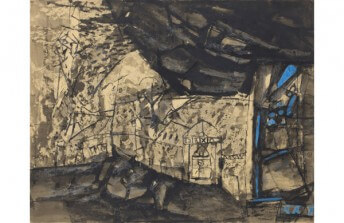

Looking back over the prolific career of Gerson Leiber, it is evident that he was not beholden to any particular aesthetic style. Many of the works he made in the 1940s and 50s share a visual language with Abstract Expressionism, and yet many other works that he made during that same period, like his 1957 etching “Under the El,” are purely figurative studies of people, places, and things. As the years tumbled onward, Gerson experimented with almost every imaginable abstract and figurative approach to image making, including Geometric Abstraction, Color Field Painting, and Lyrical Abstraction. He made Cubist-inspired drawings in the 1990s, and Post-Impressionist landscapes in the late 1960s. It is also clear by looking over his oeuvre that Gerson was not beholden to any particular medium. He created paintings, prints, drawings, and sculptures, and also frequently collaborated with his wife on projects. The two even held many dual exhibitions together. The juxtaposition of her handbags alongside his paintings portrayed a uniquely Modernist vision.

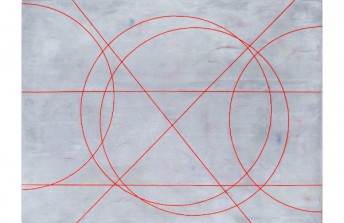

Gerson Leiber - Passionately Purple, 2014. © Leiber Collection

Despite the fact that Gerson was impossible to nail down in terms of a style, medium, or aesthetic position, he still managed to create a distinct visual language that made his work recognizable. For example, he was a master of modern compositional harmony. His sensibilities about how to make a balanced image were so keen that it simply did not matter what his subject matter was, or what techniques he was using—every picture he created expressed a sense of balance that let viewers know it came from his hands, and from his time. Another aspect of his work unique to him is the brush work. He had a way of applying paint that was perfectly controlled, and yet despite the fact that the marks he made were carefully applied, the forms and figures he painted seem energized, free, often even chaotic. It seems antithetical that someone so practiced and controlled in his technique could make images that seem so alive, but such was his skill. His craft communicated his personality—a mixture of intense discipline and simultaneous unfettered joy.

Gerson Leiber - The Giddy Riot of Spring, 2013. © Leiber Collection

The Handbag Tales

Judith Leiber never considered herself an artist, although it is purported that Andy Warhol once told her that her handbags were works of art. She is said to have responded by correcting him—calling herself an artisan. She was focused only on making the very best bags that could be made. She created about 100 unique designs over the course of her career. Many began as simple cardboard molds, which she formed by hand. The cardboard was then sent off somewhere, usually to Italy, to be fashioned out of metal. The piece was then returned to the United States, where the finishing touches—often jewels or gilding—would be applied by hand. Despite her relatively low output, her reputation was unmatched in the world of high fashion. The handbags designed by this artisan, who like her husband was born into poverty and struggle, were bought by royalty, First Ladies, and business tycoons. They were sold in the best establishments, and cherished by collectors of the finest objects in the world.

Judith Leiber - Slide Lock Clutch, photo via hanker.com

The Leibers were also avid collectors of things made by other people. Ninety-one pieces from their personal collection of art and artifacts from China, which spanned nearly 2,000 years of history, was auctioned off in March 2018 by Sotheby’s, bringing in more than $1.3 million. Their drive to collect was perhaps inspired by the same underlying quest as their drive to create, what Gerson once called his “long search for clarity, honesty and beauty.” That same search is evident in the hundreds of artworks Gerson created, which encompass abstraction, figuration, and everything in between. He and Judith examined the full range of contemporary life, and despite firsthand knowledge of what is despicable about humanity, they reflected back to us something beautiful, exotic, and full of hopeful aspiration. In 2005, the couple even built a museum in which to display their work together. It is located across the street from the farmhouse they bought together in 1956, in Springs, New York, not far from where the couple was buried together, on the same day.

Featured image: Gerson Leiber - The Simple Swagger of Spring, 2014. © Leiber Collection

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio