Georg Herold and The Luminous West at Kunstmuseum Bonn

Oct 4, 2017

Most people would probably categorize Georg Herold as a member of the so-called “older generation.” He is 70 years old, after all. And as a matter of fact, seven years ago the Kunstmuseum Bonn officially strapped Herold with that unfortunate and somewhat meaningless label when they included him in an ambitious group exhibition called The Luminous West. That exhibition featured the work of 33 artists, all of whom hailed from the Rhineland / North Rhine-Westphalia region of Germany. The goal of the show was to establish a cohesive vision of the aesthetic heritage of this part of Germany, and to tie it to a predictive examination of what the future of the region might hold. To accomplish this monumental task, the museum adopted a unique curatorial approach. First, they charged their five-person academic team with the job of selecting 19 artists who represented, in their words, “the older generation.” The team began with what they called the “historical core” of the region, which was comprised of five artists: Joseph Beuys, Sigmar Polke, Imi Knoebel, Gerhard Richter and Blinky Palermo. They then selected 14 more “older” artists, among them Georg Herold. Next, the museum invited these so-called “older” artists, or at least the ones who were still alive, to recommend artists from the “younger generation” whose work they believed warranted inclusion in the exhibition. Since he was 63 at the time, it perhaps seems like no insult that Georg Herold was selected as a representative of the older generation. But nonetheless, something about that designation seems wrong. It was not that long ago that Herold was brand new on the scene. And to this day his work remains fascinating, fresh, witty, irreverent and provocative—in many cases, far more so than that of the chronologically younger artists who supposedly represented the future in The Luminous West. That fact is brought sharply into view by the new monographic Georg Herold exhibition currently on view in that same space, the Kunstmuseum Bonn. The work remains dynamic, and continues to represent the bleeding edge. It makes me wonder if perhaps biological age should not be the sole measure of “oldness” in the arts. As Herold demonstrates, it is sometimes with the passage of time that the best ideas and most powerful works emerge from an artist, and the full meaning and potential of earlier work is finally revealed.

A Late Entry

Georg Herold was born in 1947 in Jena, Germany, a university town of about 100,000 inhabitants. His early training was as a blacksmith apprentice, after which he attended university and began to study seriously to become an artist. He first studied at the University of Art and Design Halle, in the town of Halle, nearby where he grew up. Then he moved to the southern part of the country, to Munich, where he attended the Academy of Fine Arts from 1974 through 1976. Next, he went north to Hamburg, where he studied at the University of Fine Arts under Sigmar Polke from 1977 through 1981. While he was in Hamburg, Herold made the acquaintance of several other student artists, most prominently among them Martin Kippenberger and Albert Oehlen, who had already started making a name for themselves with their punk approach to making art.

Together with these new wild ones, Herold became dubbed as one of the emergent “bad boys” of the 1980s German art scene. By the time he graduated from university, Herold was 34. Nonetheless, he was consideredpart of the new, young and brash generation. One of the “bad boys” did not survive long. Kippenberger died in 1997 at age 44, but in his brief career grew to exude enormous influence over the art world, and almost singlehandedly re-invented what it meant to be a contemporary artist. Oehlen is still active today as an artist and a teacher. His abstract paintings are beloved, and his investigations into process have proven to be enormously influential over emerging generations of artists. And then there is Herold, the oldest of the “bad boys.” He took the longest to come of age, and in some ways has resisted categorization the longest. As he once said, “I intend to reach a state that is ambiguous and allows all sorts of interpretations.” True to that aim, his oeuvre defies any and all categorization, and no one single work within it has yet to be successfully diagnosed.

Georg Herold - Untitled (Caviar), 1990, Caviar, lacquer, ink on canvas, 31 1/2 × 43 1/4 in, 80 × 109.9 cm, photo credits Magenta Plains, New York

Georg Herold - Untitled (Caviar), 1990, Caviar, lacquer, ink on canvas, 31 1/2 × 43 1/4 in, 80 × 109.9 cm, photo credits Magenta Plains, New York

Sticking With It

The first artwork for which Georg Herold is remembered was a thin slat of wood, the type used in construction, screwed to the wall. He called the piece Präsentation der ersten Latte, or Presentation of the first Plank.The work was produced in 1977, while he was still in school, for an assignment in a class taught by Sigmar Polke. The work was, in strict formal terms, undeniable. It represented line and form. As a three-dimensional object hanging on the wall, it challenged the roles of painting and sculpture. It was both minimal and conceptual. Its title implied something ceremonial. Its history as a material implied that it was a component of something larger to come. Its status as a found object invoked Marcel Duchamp and Robert Rauschenberg. But there was also something whimsical about it, and perhaps something absurd.

But in time, the title of that first piece would prove to be prophetic. Herold has again and again returned to the material of construction planks. He has used them in larger sculptures, he has hung them on the wall in different configurations, he has used them as supports for paintings and other works, and he has used them as raw materials in the construction of a series of haunting, figurative sculptures. To construct these forms, Herold binds construction planks together with thread and screws. He then stretches canvas over the bound sticks to create a sort of cocoon over the form of a human body. He allows the canvas to dry and shrink over time then he paints and lacquers the form. In some cases he then makes limited edition bronze castings of the forms. Seen in context of his early work in that class with Sigmar Polke, these figurative forms are poetic in their depth of potential meanings. But even without knowledge of their material essence, their presence evokes a range of emotions, from suffering to sensuality. They are both humanizing and dehumanizing, and call forth myriad interpretations, from images of dance to images of death.

Georg Herold - Untitled, 2011, Batten, canvas, lacquer, thread and screws, 115 x 510 x 65 cm, image © Saatchi Gallery, all rights reserved

Georg Herold - Untitled, 2011, Batten, canvas, lacquer, thread and screws, 115 x 510 x 65 cm, image © Saatchi Gallery, all rights reserved

Caviar and Bricks

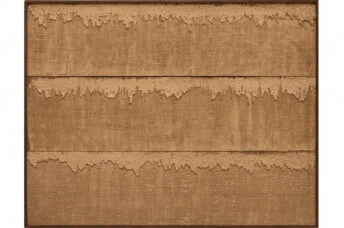

Another body of work for which Herold has become known is a series of paintings in which fish roe is used as the primary medium. These abstract caviar paintings possess a tranquil, natural quality in the vein of Korean dansaekhwa paintings. They are nearly monochromatic, lightly textured, and beautiful. But it is their medium that raises questions. The millions, perhaps billions of fish eggs that went into their making mean they are literal killing fields. They potentially represent literal wasted potential. Then again, caviar is just food, and not exactly necessary food at that. It is an expensive luxury. There is potentially much to discus about whatever message these paintings send about commerce, art, and exploitation. Then again, maybe there is nothing to say. Maybe they are simply pretty paintings.

Georg Herold - Untitled, 2011, caviar (numbered), acrylic, lacquer on canvas, 2 parts, each 350 x 203 cm, image courtesy Galerie Bärbel Grässlin

Georg Herold - Untitled, 2011, caviar (numbered), acrylic, lacquer on canvas, 2 parts, each 350 x 203 cm, image courtesy Galerie Bärbel Grässlin

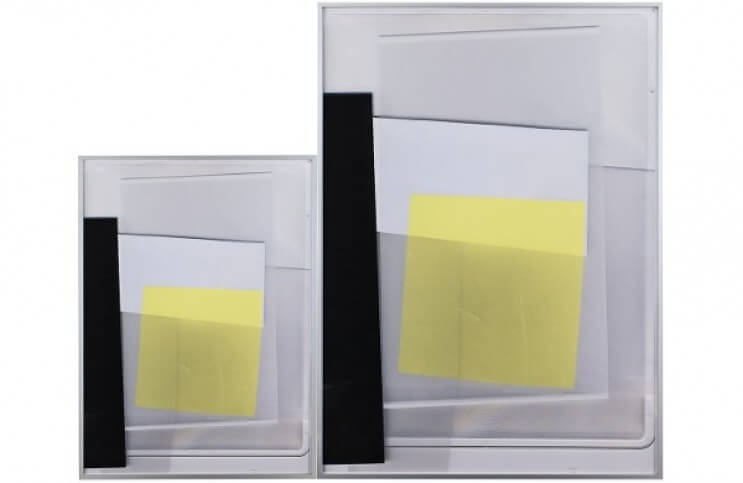

Another material to which Herold returns frequently is bricks. He attaches bricks directly to the stretched canvas surfaces of his paintings. The weight of the bricks often pulls down on the surface, stretching it and making wrinkles and ripples in the fabric. The appearance is often of a partially ruined work of art. There is tension inherent in the piece as viewers watch and wonder whether the bricks will eventually fall. These pieces seem like disasters waiting to happen. They are also fascinating examinations of materiality, texture, dimensionality and space. They are funny, and in a way they even have a mocking manner about them. They are also sublimely ambiguous. There is a great chasm between what they show us and what they tell us. Then again, they are just a construction, another step forward from the presentation of the first plank. Most notably, they are fresh. They are continued evidence that Georg Herold is not an artist who deserves to be labeled as part of any older generation. Respectfully, in fact, no living artist is.

Georg Herold at the Kunstmuseum Bonn is on view through 7 January 2018.

Featured image: Georg Herold - Herrenperspektive (Men's Perspective), 2002, Sculpture of roof battens, glass and twine, 235 x 60 x 365 cm, photo © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2016, Arp Museum Bahnhof Rolandseck, photo: Galerie Grässlin

All images used for illsutrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio