Abstract Moments in Charles Demuth Artworks

Aug 16, 2016

To say something is American doesn’t mean it is only American. America is like a metaphysical blacksmith’s workshop where humanity comes to shape things. It is where people and ideas from around the world find their fullest and freest expression. The painter Charles Demuth is considered to be the founder of Precisionism, the first American abstract art movement. But what does that mean? Was it American because Demuth was American? Was it his subject matter, his style, his aesthetic or his ideas that were American? To understand, we have to go back to the source; back before Minimalism, Color Field Painting and Abstract Expressionism; before Judd, Martin, Calder, Pollock, and all the other brilliant, prolific characters of American abstract art. We have to go back to a small town in Amish country, where, from a second story studio in his family home a frail Pennsylvania kid started an aesthetic revolution that helped shape American abstraction for generations to come.

Charles Demuth, All-American

The Demuth family’s American credentials stretch all the way back to Colonial times. Six years before American Independence, Christopher Demuth opened the Demuth Tobacco Shop in a 600-square foot shop on East King Street in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. A generation later, Christopher’s son Jacob bought the inn next door to the tobacco shop and converted it to a home for him, his parents, his wife Eliza and the 18 children in his care. By the time Charles Demuth was born in 1883, his family had lived in that inn for nearly a century. They still owned the tobacco shop, too, which continues to operate today as the oldest shop of its kind in the United States.

Charles Demuth - Bermuda, Masts and Foliage, 1917. Watercolor and graphite on wove paper, Overall: 10 x 14 in. (25.4 x 35.6 cm)

Charles injured his hip at age four and never fully recovered, relying on a cane for most of his life. But it was while bedridden from that injury that he began painting. He would eventually study art at two universities and travel the world, befriending some of the most influential artists, writers and cultural icons of his day. But he always returned to use that family house on East King Street in Lancaster as his studio for the rest of his life, painting in a room that overlooked the garden.

Charles Demuth - Bermuda: Houses, 1917. Watercolor and graphite on wove paper, Overall: 10 x 14 in. (25.4 x 35.6 cm). ©2018 Estate of Charles Demuth

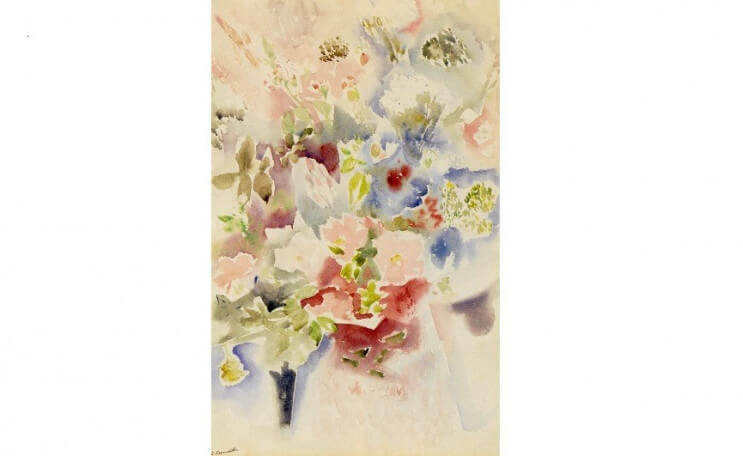

Flower Power

From the beginning Demuth painted what he saw, starting with the flowers his mother tended in the backyard back in Lancaster. In his watercolor Allover Flower Pattern, painted in 1915, the roots of his Modernist sensibilities are clear, as he sought not to capture the precise forms of the flowers but to express their luminosity and ephemeral beauty. His success at capturing the beauty of flowers became evident while exhibiting his paintings in New York, where he attracted the attention of Alfred Stieglitz and perhaps the most famous Modernist flower painter, Georgia O'Keeffe. O'Keeffe and Demuth struck up a friendship, and when Demuth died of complications from diabetes at age 51 he bequeathed to her many of his paintings, and she diligently placed in appropriate museum collections.

Charles Demuth - My Egypt, 1927. Oil, fabricated chalk, and graphite pencil on composition board. 35 15/16 × 30 in. (91.3 × 76.2 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Purchase, with funds from Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney 31.172

In addition to Stieglitz and O'Keeffe, Demuth associated with many other important characters in the early 20th Century cultural scene. While studying art in Pennsylvania, he began a lifelong friendship with the poet William Carlos Williams. While summering in Provincetown, Cape Cod, he met and began collaborating with the playwright Eugene O'Neill. He was immersed in the Harlem Jazz scene, and he often traveled abroad, frequently visiting Bermuda as well as Paris, where he was exposed to the Modernist concepts surrounding Cubism, Futurism and other abstract art movements.

Charles Demuth - Incense of a New Church, 1921. Oil on canvas

Roots of Precisionism

By 1916, the multitude of experiences to which Demuth had been exposed started to manifest in a distinct evolution to his visual language. He was inspired by Cubist planes but not the Cubist examination of perspective. He was informed by Italian Futurism’s use of angles and lines, but lacked the Futurist obsession with movement and speed. The style expressed itself in a series of watercolors Demuth painted while in Bermuda, in which organic elements are reduced to flowing, amorphous forms and architectural forms are reduced to geometric angles. The aesthetic is simultaneously urban and rural, cosmopolitan and rustic, vibrant and stoic, figurative and abstract.

Over the next few years, Demuth distilled his visual language down even more to create a bold new vision of his era. In paintings such as Incense of a New Church, he exaggerated urban architectural geometry to create dark, looming forms that are surrounded by and spewing abstracted clouds of pollution. The hard-edged lines and flat surfaces in these works led Alfred H. Barr, director of the Museum of Modern Art, to coin the term Precisionism. Fluctuating between abstraction and figuration, Demuth used this vibrant aesthetic to express the dominance and power of the new shapes taking over the American landscape.

Charles Demuth - I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold, 1928. Oil, graphite, ink, and gold leaf on paperboard (Upson board). 35 1/2 x 30 in. (90.2 x 76.2 cm). Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949

At the height of his Precisionist phase, Demuth painted what would become his most famous painting; a work based on the poem “The Great Figure,” written in 1921 by his friend William Carlos Williams. The poem reads, “Among the rain and lights I saw the figure 5 in gold on a red firetruck moving tense unheeded to gong clangs siren howls and wheels rumbling through the dark city.” With vibrant energy and flash, Demuth’s painting captures all of the poem’s excitement, chaos, noise and power.

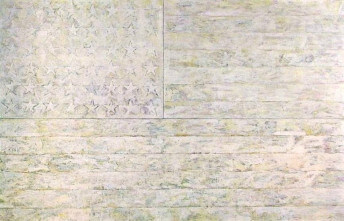

The way this painting deals with symbolism, context and formal elements like color, form, surface and line explain why Demuth is considered the founder of the first American Abstract art movement. It appropriates an existing cultural work and converts it into an art object. It removes a typographical form from its symbolic reference point, abstracting it into something purely aesthetic. It uses additional text fragments in a way that further confuses the image’s meaning. It uses the colors gold, red, white and blue as subject matter rather than decoration. These ideas were the foundation for the work of the generation of American artists immediately following Demuth’s death in 1935. American artists such as Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol and Donald Judd, and the philosophies of Conceptual Art, Pop Art and Minimalism, were all influenced by Demuth, and especially by this particular painting. The meaning of it may be ambiguous, but this image and the movement it defined are purely American.

Featured Image: Charles Demuth - Allover Flower Pattern, 1915. Watercolor on paper. 17.75 x 9.38 in.

By Phillip Barcio