Paul Nash and History Within the Abstract

Jan 18, 2017

British painter Paul Nash is not normally mentioned in conversations about abstraction. But his Modernist, sometimes-surreal images reveal glimpses of the profound abstract concepts often lurking in plain sight in the natural world. His body of work, which spans from just prior to World War I until just after World War II, incorporated what might be called a conservative abstract language. Rather than drawing on pure abstraction or exploring formal abstract elements like color, line, or light, he rooted his work in the classic, figurative landscape in hopes of establishing a broader definition of what abstraction might be. He intended his paintings to spark ideas; not about scenery, but about the ancient, eternal relationships between the forces of time, nature, humanity, culture, life and death.

Early Crises

In 1910, Paul Nash enrolled as a student at the Slade School of Art, where he quickly found himself associated with a group of young artists collectively referred to by the academy as its Second Crisis of Brilliance. They possessed a rare combination of exceptional talent, openness to European Modernism, and a willingness to experiment, putting them in opposition to the curriculum and the abilities of the faculty of the school. Nash and the others were the enthusiastic Modernist vanguard in a culture that wanted nothing to do with making things new.

As a current Paul Nash retrospective at the Tate demonstrates, the work he was making at that time does not seem so threatening today. He was painting English landscapes, attempting to capture what he referred to as their genius loci, or spirit of place. He was fascinated by the primeval megaliths dotting the English countryside, which he regarded as manifestations of the ancient relationship between humans and nature. Perhaps what was threatening was that he was not just interested in copying nature, but also in expressing the larger abstract messages contained therein.

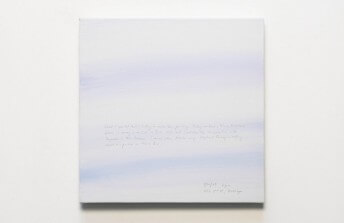

Paul Nash - Wire, 1919. © Imperial War Museum, London

Paul Nash - Wire, 1919. © Imperial War Museum, London

A Terrible New World

Four years after he entered art school, Nash, along with his entire generation, had his future interrupted by the outbreak of World War I. Nash voluntarily enlisted in the Artists Rifles, a domestic regimen first formed in 1859 and composed mostly of artists sworn to defend the home front. But as the war dragged on he ended up being sent to the Western Front, the primary theater of combat on the European mainland. It was there, as a 2nd Lieutenant, that Nash witnessed firsthand the horrors of war.

Serendipitously, three months after arriving at the front, Nash fell in a trench and broke a rib. While he recovered in London his regimen was attacked and almost completely annihilated. Deeply troubled by everything he had seen, he became determined to do what he could to end the war. While still recuperating he held an exhibition of images he made of the carnage at the Front. They were shocking for many people who had no concept of the brutality and devastation of the war. The works made such an impact that when he recovered he was sent back to the Front to serve as an official war artist. He spent the rest of the war painting detailed images of the destruction in hopes he could sway the public to end the fighting.

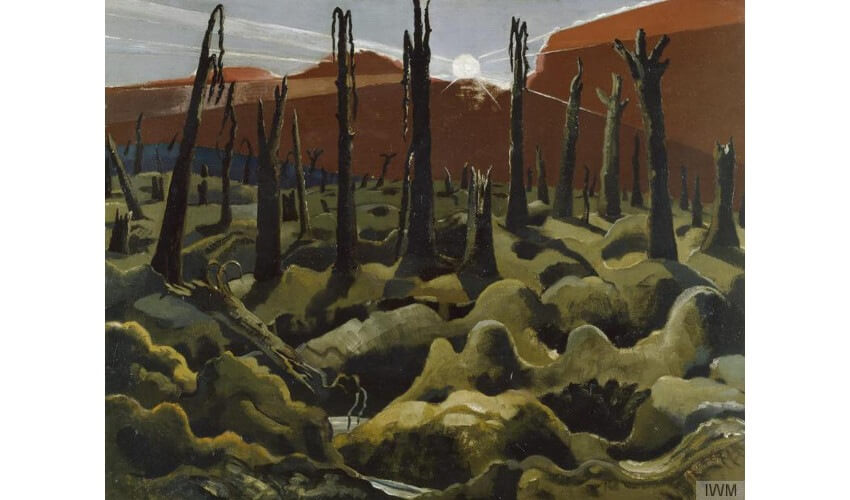

Paul Nash - We Are Making a New World, 1918. © Imperial War Museum, London

Paul Nash - We Are Making a New World, 1918. © Imperial War Museum, London

Redefining Abstraction

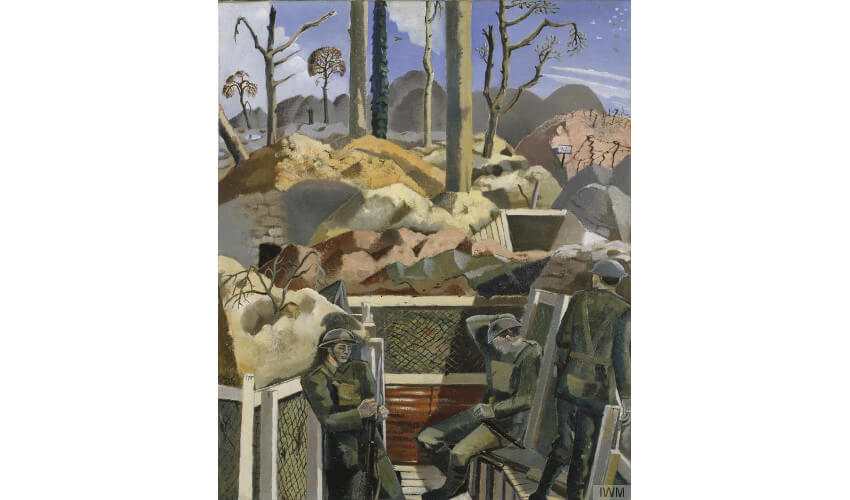

The war paintings Nash made are starkly realistic. And yet beyond their figurative content they possess undeniable conceptual layers. For example, on the surface, the painting Spring in the Trenches, Ridge Wood, 1917 portrays a purely realistic image of a few soldiers entrenched within a battle-scarred natural landscape. But the pastel color palette, the birds flying absentmindedly overhead, and the puffy white clouds innocently meandering by suggest the profound idea that while humans might temporarily be able to destroy nature, Nature with a capital N will outlast our rage, and will continue on after we are gone.

In his later war images, Nash began experimenting with the reduction of the visual elements of the natural world, paring them down to simpler shapes and forms. Although he never transitioned into pure abstraction, he saw that by reducing certain parts of his visual language he could connect with something universal, beyond the figurative. About this evolution, he said, “I discern among natural phenomena a thousand forms which might, with advantage, be dissolved in the crucible of abstract transfiguration.” And yet, he said, “I find I still need partially organic features to make my fixed conceptual image.”

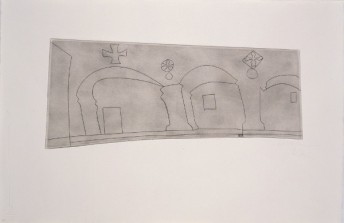

Paul Nash - Spring in the Trenches, Ridge Wood, 1917-1918. © Imperial War Museum, London

Paul Nash - Spring in the Trenches, Ridge Wood, 1917-1918. © Imperial War Museum, London

Unit One Group

By the time the war ended Nash had become famous in Britain for his war paintings. Their abstract elements were not what most people responded to. Rather he was revered for showing the factual destruction, as if he was a journalist. Suffering from the psychological and physical effects of the war, he retreated to the countryside where he attempted to heal himself physically and spiritually. He returned to figurative landscape painting, immersing himself in its calming power. But as he recovered he became more interested in a problem he perceived in British culture: its unwillingness to embrace and comprehend the deeper importance of modern trends in art.

In an effort to engage directly with the British public, Nash formed an avant-garde artist collective called Unit One. Twelve other architects, painters and sculptors joined him, including Ben Nicholson, Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth. The group held one exhibition. The works Nash showed in it are among his most abstract. They show Modernist forms intermingling with natural environments in mysterious, almost Surrealist compositions. Though it was a short-lived experiment, Unit One caused the public to take notice, and its impact on British Modernism was immediately felt.

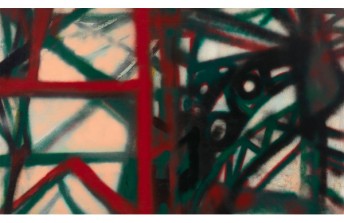

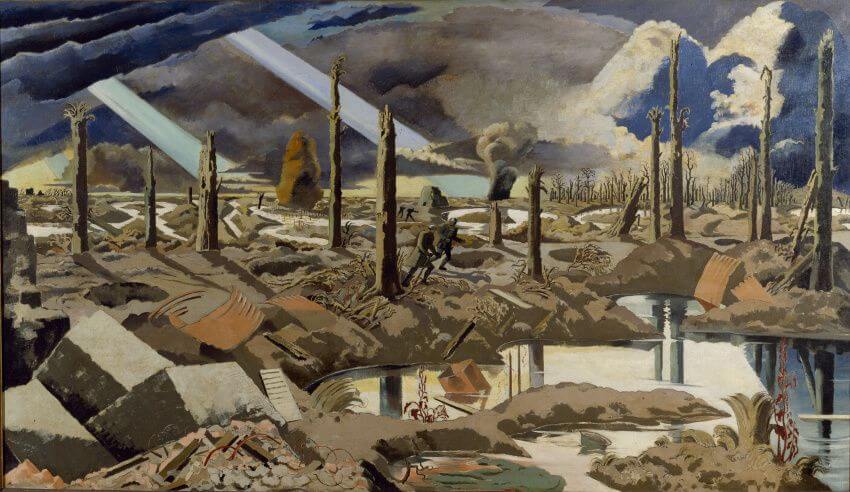

Paul Nash - The Menin Road. 1919. © Imperial War Museum, London

Paul Nash - The Menin Road. 1919. © Imperial War Museum, London

Abstract Figurative History

At the height of his fame, Paul Nash was once again enlisted as a war artist, this time in World War II. The paintings he made of that conflict are among his most famous works. They show a mature combination of the many influences that defined his career. They show figurative landscapes, reductive shapes, and uncanny conglomerations of quasi-surreal objects and beings. They raise questions about the relationships of machines, humans and nature. They portray the carnage and destruction of war, while simultaneously suggesting nature will always endure.

Looking back over his oeuvre we can see that Paul Nash was never just painting realistic landscapes of particular places in time. He was also painting the landscape of his mind, as embodied by the serenity of nature and the horrible beauty of death. He often did capture genius loci, the spirit of place, even when that spirit was unmistakably evil. But as he once said, “to find, you must be able to perceive. There are places, just as there are people and objects, whose relationship of parts creates a mystery.” Somewhere in his images of life and death, of modern relics side-by-side with relics of bygone civilizations, a mysterious connection is made; one that reminds us history predated us and will outlast us, and that though we are part of nature, we cannot overcome it; on the contrary, it waits always to overcome us.

Featured image: Paul Nash - The Ypres Salient at Night, 1918. © Imperial War Museum, London

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio