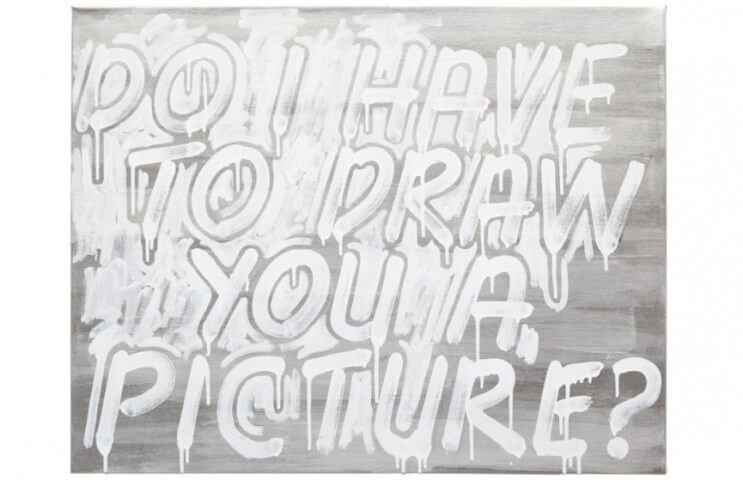

Mel Bochner and The Different Side of Language

Sep 11, 2016

Words are a precious resource. They are a storehouse of meaning. They enable societies to develop cultures. They help us express feelings, explain the past and make future plans. And yet words can also easily be misused, causing confusion or even disaster. The conceptual artist Mel Bochner has devoted much of his career to exploring the medium of words. Not to say Bochner is a writer, exactly. Rather, he engages in something like an abstract aesthetic version of semiotics. Semiotics is the study of symbols; how they are used, what they communicate, and the various ways they might be interpreted. Bochner creates aesthetic phenomena that use symbolic elements such as words in ways unrelated to their usual context. By appropriating common symbols and presenting them as abstractions, Bochner allows viewers the opportunity to interpret these symbols and their context in new ways. After all, what are written words and symbols but forms, texture and patterns arranged on a surface or in space? Bochner has long been careful not to explain his art. It certainly opens itself up to literal interpretation, since it uses language, but it can also be interpreted conceptually. By not revealing his full intentions he opens the work up to a much wider range of experience. He creates opportunities for us to study each other while we study his art, turning every exhibition into a semiotics experiment from which unlimited levels of meaning may emerge.

The Power of Ideas

In a world full of contradictory information, how do we know what to believe? Epistemology is the study of the difference between justifiable beliefs (known as “truths”) and unjustifiable beliefs (known as “opinions”). Epistemologists know the most important truth of all: that the human mind is capable of convincing itself to believe anything. With the right kind of persuasion people can be convinced to doubt their own existence. This fundamental characteristic of our nature is what gives us our imagination. It is what allows us to accumulate and share knowledge, to learn, to create, and to expand the capabilities of our species. But it is also what allows us to become delusional, to ignore obvious threats, and to be turned against each other with falsehoods.

The essence of epistemology is the same as that of conceptual art: ideas. Every belief, every building, every book, every bomb and every bullet was once just an idea in somebody’s head. Epistemologists analyze the ways humans interact with specific ideas; they do not challenge the metaphysical basis for those ideas or attempt to manifest the ethereal natures of ideas as concrete phenomena. But when conceptual art emerged in the 1960s, its goal was precisely that. As explained by Joseph Beuys, one of the pioneers of the movement, the idea is the most important part of a conceptual work of art. Said Beuys, “the rest is the waste product, a demonstration. If you want to express yourself you must present something tangible. But after awhile this has only the function of a historic document. Objects aren’t very important any more. I want to get to the origin of matter, to the thought behind it.”

Mel Bochner and his exhibition Working Drawings And Other Visible Things On Paper Not Necessarily Meant To Be Viewed As Art, 1966. © Mel Bochner

Mel Bochner and the First Conceptual Art Show

Born in Pittsburgh in 1940, Mel Bochner studied art at Carnegie Mellon University in the earliest days of Conceptual Art. After graduating, he went on to study philosophy at Northwestern University in Illinois. When he moved to New York at age 24 to become an artist, his first job in the city was guard at the Jewish Museum, a job incidentally held by several famous artists of his generation. At that time the Jewish Museum had a reputation for showing the edgiest contemporary American art. While performing his duties, Bochner was able to browse the works of the leading Modernists. Among the works he saw there was White Flag by Jasper Johns, a painting famous for transforming an iconic symbol into an abstract form by changing its context.

Mel Bochner - Self Portrait, 1966. © Mel Bochner

In 1966, two years after moving to New York, Bochner had his first solo show in the gallery of the School of Visual Arts, where he had taken a teaching job. The exhibition drew heavily on Johns’ concept of re-contextualizing common symbols as objects of art. For the exhibition, Bochner collected copies of drawings, receipts, technical papers and other printed materials and arranged them into four black binders. He presented the binders on pedestals and titled the show Working Drawings And Other Visible Things On Paper Not Necessarily Meant To Be Viewed As Art. It was a groundbreaking show. Although Joseph Beuys had debuted his conceptual piece How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare a year earlier, the Harvard art historian Benjamin Heinz-Dieter Buchloh nonetheless declared Bochner’s show the first conceptual art exhibition, perhaps since Beuys’ work was technically a performance.

Mel Bochner - Repetition: Portrait of Robert Smithson, 1966

What is In a Word

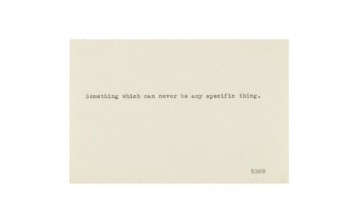

Following his breakout exhibition, Bochner began making what he called “portraits,” which were sheets of graph paper filled with synonymous words. The portraits could be interpreted literally according to whatever visceral reaction the words elicited in a viewer. Or, as with the materials in his binders, they could be seen simply as abstractions. His Self Portrait listed 23 synonyms for self alongside 23 synonyms for portrait. The shape of the arrangement of the words on the paper vaguely resembles that of a human head.

Mel Bochner - Measurement: 180 Degrees, Twine, nails and charcoal on wall, 1968. © Mel Bochner

Many of the portraits Bochner made were of artists he admired or was friends with. The portrait he made of the land artist Robert Smithson consists of synonyms for repetition arranged in a repetitive aesthetic pattern. It is tempting to view this piece simply in terms of its aesthetic qualities, focusing on the positive and negative space on the surface, same as a viewer might interpret the elements of one of Smithson’s own works, like the basalt rocks and exposed lake bottom that together make up Smithson’s Spiral Jetty.

Mel Bochner - Measurement: Room, tape and letraset on wall, 1969. © Mel Bochner

Measurements of Success

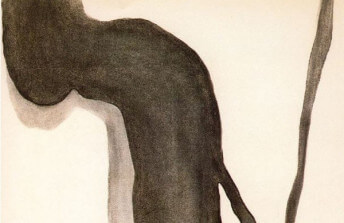

Our interpretations of many of the early works Bochner made rely heavily on the specific messages normally carried by the words and images he appropriated. If we can break free of that influence and consider his symbols purely as aesthetic objects we can experience new levels of contemplation. For example, we can marvel that words and letters exist at all and wonder at the various forms they have taken, and contemplate the meaning of the symbols other cultures have evolved to convey similar meaning.

In a series of exhibitions Bochner began in 1968, he addressed the phenomena of measurements. Rather than using a gallery space to exhibit objects, he used tape, string and Letraset markers to document the measurements of various architectural elements within the space. Rather than performing their usual utilitarian function, the measurements became abstract markings that could be viewed purely as aesthetic phenomena. Also, by drawing the attention of viewers to the invisible dimensions of their surroundings rather than to an object within their surroundings, the measurements accomplished what artists such as Lucio Fontana sought to achieve, which was to turn space into form.

Mel Bochner - If / And / Either / Both (Or), oil and casein on 28 pre-stretched canvases, 1998. © Mel Bochner

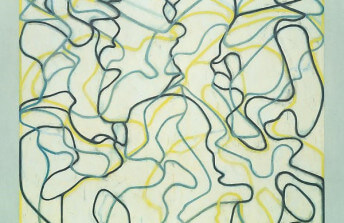

Conjunction Function

Those who view Bochner’s work respond in many different ways. Bochner once recalled having the experience of watching war veterans tearing up at the sight of his painting composed of synonyms for the word “die.” Some viewers interpret all known symbols as concrete and respond emotionally to their content, regardless of context. But others seem to be able to respond to Bochner’s symbols as only forms: placeholders for medium and texture on a surface. And it is also possible to consider a third interpretation, one that pertains not to the meaning of the symbols Bochner uses but to the metaphysical value of his overall concept.

Connections occur whenever human beings see images. We call those connections conjunctions; they bridge one experiential phenomenon with another. We take for granted throughout our daily lives that we have trained our brains to appropriately interpret conjunctions so we can survive in the complex aesthetic environment we inhabit. We have little time during our quest for sustenance to stop and consider whether we are satisfied with our construct of reality. By re-contextualizing the symbols and signs of our culture Bochner gives us an opportunity to pause, to consider our social construct from new perspectives, and to self-reflect. He gives us a safe, intellectualized environment, removed from the peril of everyday life, in which to ask important questions such as what are we doing, what are we saying, what are we making, and what does any of it mean?

Featured Image: Mel Bochner - Do I Have to Draw You a Picture, 2013. © Mel Bochner

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio