James McNabb - Seeing Cityscapes in Wood

Sep 11, 2017

James McNabb is either living out the ultimate fantasy or the ultimate nightmare of every young artist in the world. Several years back, McNabb created a collection of sculptural pieces out of recycled wood for his MFA thesis project. The main works in the show were a free standing circular form, a hanging spherical form, and a freestanding tabular form. Each was created from smaller, geometric, abstract, wooden, tower forms, but when fused together in groups, the tall, skinny, geometric towers took on the character of something else entirely: a city. After his thesis show ended, McNabb initiated a Kickstarter campaign to raise funds for a followup project called The City Series, which extended his basic idea into a larger series of similar works. As McNabb described it on Kickstarter, The City Series is “a collection of wood sculptures that represent a woodworker's journey from the suburbs to the city. Each piece depicts the outsider's perspective of the urban landscape. Made entirely of scrap wood, this work is an interpretation of making something out of nothing. Each piece is cut intuitively on a band saw. The result is a collection of architectural forms, each distinctly different from the next.” The campaign exceeded its goal, and since 2013, McNabb has been exhibiting the work that grew out of it in art exhibitions all over the world. The work has been written about in dozens of publications, and on 2 September 2017, a solo exhibition of the work opened at Galerie Magda Danysz in Paris. And that all sounds wonderful, right? His graduate school thesis show is making McNabb famous. He is living the dream. But it is also possibly tragic, because it seems like everybody, including McNabb, is getting it wrong.

Artist, Designer, Craftsman

It is safe to assume that James McNabb considers himself an abstract artist. Back in 2013, on his Kickstarter page, McNabb described himself as an “artist, designer, craftsman.” The word artist came first. For that reason alone we should presume he wants his work to be interacted with by viewers as though it is primarily art. Furthermore, when he described his work, he did not say, “These are buildings and this is a city.” He was more open. He described the pieces as “wood sculptures that represent” something and “depict” something. He called the work an “interpretation.” Seemingly, that would put him in the tradition of the Brazilian Neoconcrete pioneer Lygia Pape, who we wrote about yesterday, who created abstract, geometric forms that suggested a line of thinking, but which also remained open, awaiting interpretation by viewers.

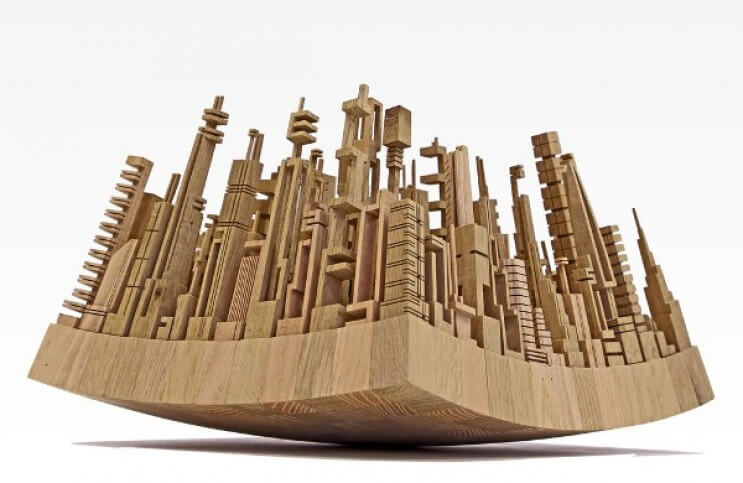

James McNabb - Untitled, City Arc (004217CA24), 2017

James McNabb - Untitled, City Arc (004217CA24), 2017

But hold on. Remaining open and awaiting interpretation is the farthest thing from what is happening with McNabb and his work. The work is being written about in the most figurative and representational terms possible. It is not being called abstract art. Rather, it is being called abstract design. And that is not only the fault of the writers. McNabb has collaborated with the global advertising firm Leo Burnett Worldwide three times to create their Agency of the Year awards, which mimic his “art,” except the forms incorporate the actual architecture of the home city of the winning agency. And McNabb also created a flat, representational model of Manhattan using his signature style, which was featured in the New Yorker Magazine. So there seems to be a disconnect. If McNabb intends his work to be read as art, and especially as abstract art, why do projects such as these? There is nothing artful about advertising awards. There is nothing abstract about a miniature wooden model of Manhattan. These things were definitely cool looking, but all they amount to is craft and design.

James McNabb - Wheel, 2015, Various Wood, 45 in. diamerer

James McNabb - Wheel, 2015, Various Wood, 45 in. diamerer

No More Explaining

When Constantin Brancusi created his first Endless Column in 1918, he described it as a “column for infinity.” He later expressed the idea in monumental form with his Infinity Tower in Romania. What the tower form means is up for interpretation. It evokes a totem pole, a skyscraper, a walking stick; or perhaps just a meaningless stack of truncated pyramids. But its value as art lies in our freedom to finish the work with our own experiences and thoughts. Louise Bourgeois also made geometric, architectural-looking towers. They could be read as buildings, especially when exhibited in a group. Or they could represent people. Or they could project multiple other meanings, again based on the experiences and personal thoughts of the viewer. This is one of the most revered, and admittedly in some cases also the most irritating, traditions in abstract art: the tradition of not explaining exactly what something is.

James McNabb - detail of an artwork

James McNabb - detail of an artwork

Openness separates abstraction from representation. It also separates artists from designers and craftspeople. Designers make useful products. They might also make beautiful products and meaningful products, but the essence of their work is utility. Craftspeople practice crafts. They make things by hand to demonstrate mastery of a traditional skill and to participate in the tradition to which that skill belongs. Artists are different. Artists sometimes employ the skills of designers, and they sometimes master their craft. But they also help us establish meaning in our lives. They help us connect with the unknown. They open up possibilities beyond what we already know and see. What I think is unfortunate is that the objects James McNabb makes could do that. If I encountered them with an open mind, they could inspire me to contemplate them and lead me to engage in larger conversations. But instead they are falling flat because before I have had a chance to meet them in the open, McNabb and a battalion of marketers have already met me halfway with the pettiest, most obvious explanation of what they are and what they mean. It is tragic because although the attention is making McNabb famous, it is also diminishing the value of his work by betraying its complexity.

James McNabb - Ack Cty Whl 1, 2017 (Left) and Ack Cty Whl 2, 2017 (Right)

James McNabb - Ack Cty Whl 1, 2017 (Left) and Ack Cty Whl 2, 2017 (Right)

Featured image: James McNabb - City Vessel, Oak, 19 x 16 x 12 inches

All images © James McNabb, all images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio